Having a deep respect for the beauty that comes from diversity, equality, and inclusivity, we…

A Walk with Geronimo

It’s Tuesday, November 3, 2020. Election Day. The end of harvest. Grape shipments have stopped. The tanks are full. The cellars smell like fermenting grapes and Geronimo is at the cellar desk filling out a work order. He’s probably filled out tens of thousands of work orders on tens of thousands of cold mornings. It’s his forty-first year. His forty-first harvest. His first harvest was in 1980. Earlier that year, Geronimo moved up from LA to Santa Rosa to live with his uncle, Domingo. Domingo worked at a winery off Guernville Road in western Santa Rosa. The winery needed extra hands for harvest, so Domingo offered Geronimo a job and Geronimo took it.

When Geronimo started, the winery was called Martini & Prati. Now, it’s Martin Ray. When Geronimo started, there were only six people working production: the winemaker Frank, Lloyd Houston, Domingo, two other guys, and Geronimo. Today, the number of employees on the winemaking and production teams has more than tripled.

Geronimo files the work order and joins me. His baseball hat is pulled low. The brim bent up, like a wave reveals mischievous eyes, often crinkling. As a COVID mask, he wears a bandana with a skeleton’s face. Wisps of a large salt and pepper beard sneak out the bottom. We are standing next to a massive stainless-steel tank, shiny, cold. We stroll past a row of massive stainless-steel tanks.

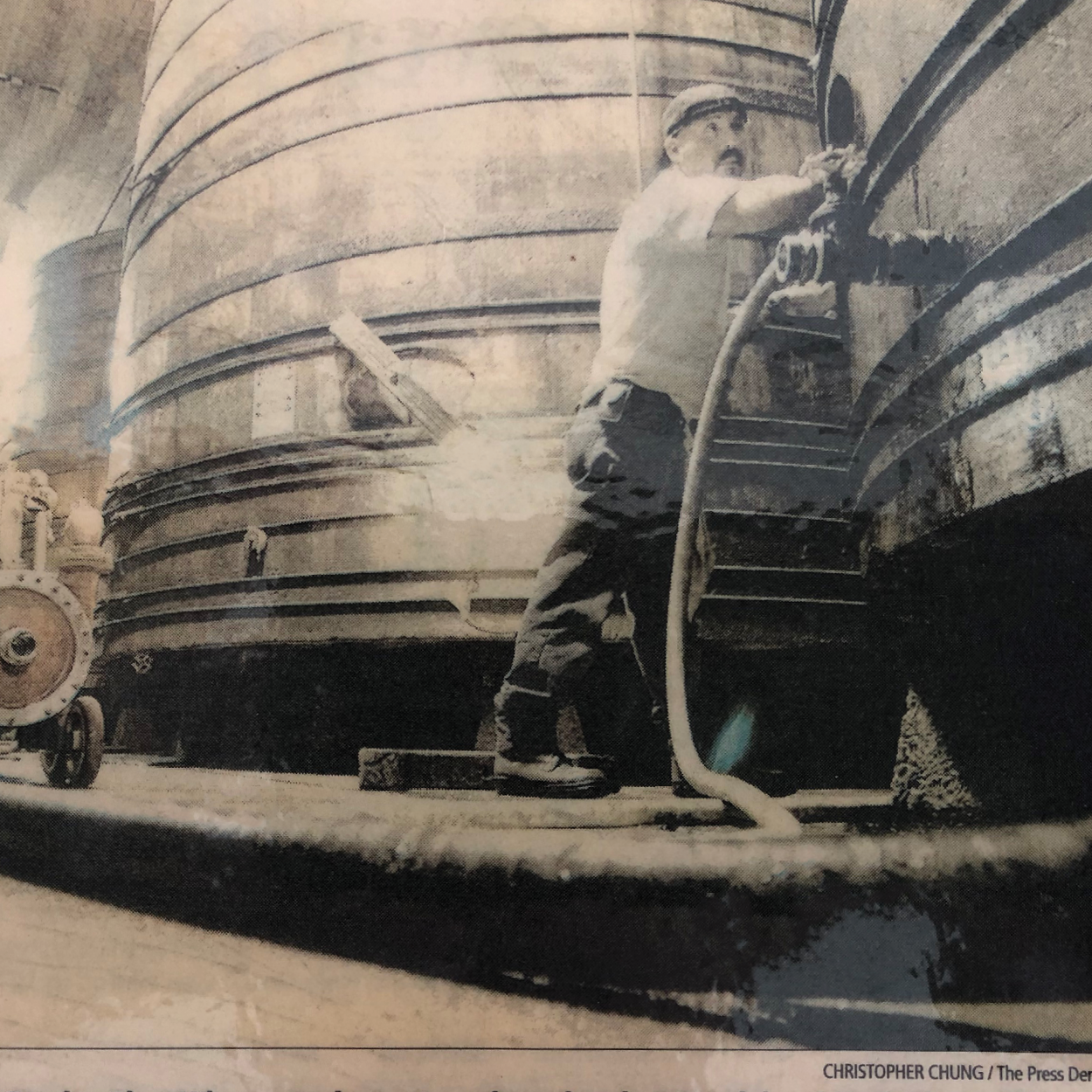

When Geronimo started, there were only two stainless steel tanks on the property. The cellars were filled with redwood tanks. The redwood tanks were installed in 1881. Redwood was used for tanks in northern California because nearby virgin coastal forests made it abundant. Also, it was durable, but had drawbacks. Geronimo says, that seeped through the tanks, so the outside of the tanks had to be cleaned every three days. The fermentation tanks weren’t refrigerated so, every day, they had to pump the wine out of the tank through a pipe within a pipe, known as a heat exchanger. The outer pipe was supposed to be filled with cold water, but they used groundwater, which, Geronimo said, wasn’t that cool. So the cooling wasn’t that cold, and then the wine went back into the tank.

When they cleaned the inside of the redwood tanks, they had to use liquid sulfur to kill fungi. Liquid sulfur is highly toxic and shouldn’t be inhaled. No matter, they didn’t wear masks. They lined the hatch with beeswax for an air-tight seal, put in about 20 pounds of liquid sulfur, twisted the hatch shut, nailed a board across it for good measure, and ran away. After a couple months, they checked to see if the sulfur had subsided. Their sulfur detector was their own noses. Once it didn’t smell like sulfur, they rinsed out the tank.

Geronimo and I have strolled to the end of the big tank room. We climb a ladder into the aging room. It’s probably 50 yards wide and 20 yards long. There are rows of barrels stacked five high. When Geronimo started, there were three 60-watt light bulbs in the entire room and only two drains that were just small holes in the floor. It was dark all day and the floors were slippery. He points to a corner obscured by a stack of barrels and says, “Tank 234 and tank 235 were there.” He will do something similar in the Barrel Room, then points to a corner where there is an emergency shower, and says, “That was tank 308”. And in the Twin Fir room, he will let me know that tank 336 was in the Southwest corner. Geronimo remembers the exact location of every tank that he’s ever worked with. Oh, and he remembers exactly how many tanks were in each part of the cellars. He says that the current aging room had twenty-four 11,000 gallon and four 6,000-gallon redwood tanks and the current open-top fermentation room housed sixteen 38,000 gallon redwood tanks. He knows the Barrel Room and the Twin Fir Room housed thirty-six open-top cement fermenters and that they were seven feet deep and could hold 25 tons of each. Once the juice was drained out, it took two guys 45 minutes to dig out one fermenter.

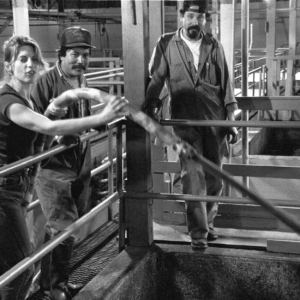

In the open top fermentation room, Geronimo tells me about the old narrow wet springy wooden catwalks that ran above tanks and he had to hunch to avoid banging his head on the rafters. Geronimo’s only injury in four decades didn’t have anything to do with a tank. He was painting a ceiling in Warehouse A. The ceiling is about twenty feet high. He was balancing at the top of the ladder; then he wasn’t balancing; then he was tipping. He landed on his hip and white paint was splattered all over his clothes. He walked with a limp and had a headache for a couple weeks, but besides that he was okay. Geronimo credits his father his longevity. He taught him not to trust things or people and to expect the worst. He also credits his longevity to a fact that he’s never asked for a raise. When Geronimo started, his salary was $2.75 per hour.

We leave the cellars and are outside, looking at the two old stainless-steel tanks that are insulated in a cross between tin foil and bubble wrap. They are afterthoughts today. The crush pads and outdoor tanks and employee parking lot are all paved. When he started, they were a meadow that Geronimo had to mow when there was nothing else to do. The Pavilion was a parking lot flanked by two garages. The patio and outdoor kitchen were a crush pad. The Bocci Court was a shipping bay. Another constant on the property, besides Geronimo, is the tasting room. It was the same building in 1980 as it is now. Under the big tree outside, they partied. Geronimo’s eyes crinkle. He tells me that, on Friday after work, they drank jugs of unfiltered wine and danced.

We are back near the workbench. The tour is almost over. Geronimo points to a vent on top of Warehouse A. It’s a vent I’ve never noticed, not that I notice vents. But this vent seems particularly unworthy of notice. It probably isn’t functional anymore. Geronimo says that during a storm in 1987, the figure of Jesus Christ appeared in its slats. I peer into the slats. Jesus Christ disappeared after the storm, Geronimo adds. I peer harder. Still no sign. When I turn back, Geronimo has disappeared between the tanks.